Economics is the study of how individuals, businesses, governments and countries make choices. They need to allocate limited resources. And they want to choose the mix that makes them happiest. Keep reading for the answers to common questions about economics during COVID-19. Will we have a recession? Is high inflation coming? Why don’t we make ventilators and masks here?

This post may contain affiliate links, which means I make a small commission if you decide to purchase something through that link. This has no cost to you, and in some cases may give you a discount off the regular price. If you do make a purchase, thank you for supporting my blog! I only recommend products and services that I truly believe in, and all opinions expressed are my own. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Please read my disclaimers for more information.

For all my articles on this theme, go to Personal Finance during the Coronavirus Pandemic.

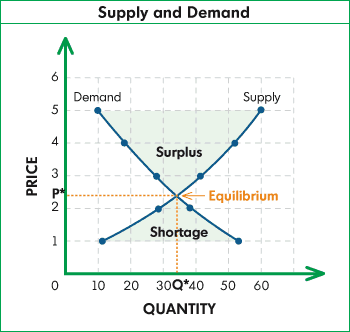

Demand and Supply, and their Impact on Prices

Economics is all about demand and supply. In general, as the price rises, people buy less of that good or service. But as prices rise, manufacturers want to sell more of that good or service.

For example, if chocolate bars were $5, few people would want to buy them, but Hershey’s sure would love to sell a lot at that price. That would lead to a surplus of chocolate bars. Then Hershey’s would lower the price to encourage consumers to buy more. Eventually the price would settle at the exact place where demand and supply are equal.

In the past month we’ve seen what happens when we have a sudden increase in demand for toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and similar products. Suddenly, demand is greater than supply, and we have a shortage. Some individuals and companies have taken advantage of that during the coronavirus pandemic. I think we’ve all heard of those guys who had a garage full of hand sanitizer to sell at several times the usual price. Recently, our Premier here in Ontario called out a high-end grocery chain for selling disinfecting hand wipes for $30 a pack.

Related COVID-19 reading:

- What Will the Economy Look Like After Covid-19?

- Experts Weigh In: Will Covid-19 Cause a Global Recession?

- What Should you do When the Stock Market Crashes?

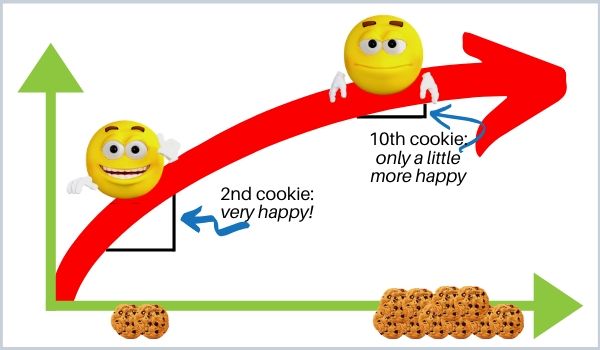

Marginal Utility

The concept of marginal utility is the additional satisfaction, or happiness, of getting one additional unit of a good or service. Most goods and services have positive marginal utility, at least in small numbers of products. That is, getting one pair of shoes makes you happy. Getting a second pair of shoes gives you more happiness. Getting a third pair of shoes still gives you more happiness. A few items have zero marginal utility. After your first haircut, you really don’t get any more happiness from a second haircut the same day.

The “law of diminishing marginal utility” states that in general, the happiness you get from one additional unit of good or service declines as you get more and more. That is, in our shoe example, the first pair made us really happy. By the time we get the 10th new pair of shoes today, our happiness is only increasing a tiny bit.

Sometimes marginal utility can become negative. Eating one cookie makes me really happy. Eating a second still makes me happy. But eating the 10th cookie makes me feel sick.

Marginal utility can be used to set prices. Stores can set pricing based on diminishing marginal utility by giving you a discount when you buy multiple items – buy the first one at full price, get 20% off the second one.

This concept of high marginal utility for the first item was used by individuals and companies selling hand sanitizer and toilet paper for far more than the usual prices, at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. The sellers knew that for households with none, they would put a high value on purchasing their first bottle of hand sanitizer, and would be willing to pay more for that.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Economic growth is measured by gross domestic product, or GDP. It is the value of goods and services produced in a country in a month or a year.

GDP = Consumption Spending + Government Spending + Investment + Net Exports

The income approach is another way to measure GDP. Logically this makes sense, because someone else’s spending becomes your income.

GDP = Wages + Rent on Land + Interest + Corporate Profits

GDP is important to economists because it measures the health of the economy. We sometimes measure it as a percentage. For instance, GDP growth is 2% in the fourth quarter of 2019. Nominal GDP is based on current prices, whereas real GDP removes the impact of inflation. Real GDP is a better way to look at growth.

You can also look at GDP per capita (per person) as a measure of standard of living, or prosperity. Real GDP growth per capita can be thought of as how much the average person’s income grew.

Let’s put these in perspective. In 2018 the U.S. had GDP of $20.58 trillion. In 2019, the GDP was $21.4 trillion. That’s a 4.1% increase over the year before. But inflation was 1.8%, so the real GDP growth was 2.3%.

In 2018 the U.S. had a GDP per capita of almost $63,000. China’s economy in 2018 was slightly larger, at US$25.4 trillion. But they have about four times the number of people, so their per capital GDP is slightly over US$18,000. This reflects a difference in standard of living between the two countries.

In 2019, the U.S. GDP per capita was about $65,500, an increase of about $2,500 per person from the year before.

Recessions and Depressions

A recession is defined as two quarters (or six months) of declining GDP growth. That is, the value of goods and services produced is LESS than the quarter before. By this measure, we only know that we’re in a recession after growth has already fallen for half the year! We might even be coming out of the recession by the time we can measure that we had one.

Recession

A recession includes several other characteristics:

- GDP growth is negative for 2 quarters

- Unemployment rises

- A loss of consumer confidence

- Stock market crash

- A rise in business failures and personal bankruptcies

- A recession usually lasts for less than one year

Depression

While there’s no standard definition of a depression it is generally characterized by:

- Lasting at least two years – GDP growth is negative for more than 24 months

- GDP growth declines by at least 10%

- Mass unemployment

- House prices fall dramatically

- Falling retail prices – inflation is negative

- Low income, or wages are falling

- Persistent lack of consumer confidence

The Great Depression of the 1930s has taught governments and central banks a lot about what not to do, and how to avoid the next depression.

Inflation

We all know that prices now are higher than when we were kids. And so-called “penny candy” hasn’t been seen in many decades. When households, businesses and government spend money hand over fist, this causes prices to rise.

Inflation is a measure of how fast prices are rising. We measure it with the Consumer Price Index (CPI). It’s calculated as a representative basket of goods and services that would be typically purchased by people like you and me. Inflation in North America has been fairly steady at about 2% for a long time, and central banks use interest rates to keep it that way. When prices start to inch up too fast, the central bank increases interest rates, which discourages spending. Recently we’ve seen big drops in interest rates in both the U.S. and Canada, as governments want to support more spending through the current crisis.

Three Reasons Why Government Stimulus Spending will NOT Cause High Inflation

There has been some question lately, will the massive amounts of government stimulus spending cause inflation later in 2020 or 2021? I believe this will not happen. For one thing, millions of households are facing a massive loss of income due to job layoffs. Many will stop spending money on anything that is not an absolute necessity. Moreover, most retail stores have closed for the near future. While shopping can still be done online, delivery times are delayed, and many items we may prefer to buy in person. Even when we’re all back to work, and those impacted by layoffs are again earning paycheques, they may be more restrained with their spending for quite some time as they catch up on paying bills.

Secondly, the stock market has taken quite a hit this year. This is a real decline in wealth. Many retirement accounts hold a significant portion of their assets in the stock market. In addition, upper- and middle-class households also hold wealth in the stock market. When they sell stocks now, they will receive less cash for that, and therefore will have less money to spend. In fact, the total value of the stock market decline is far more than the value of proposed stimulus spending.

Thirdly, interest rates have been drastically cut in early 2020. This leaves a substantial amount of room for central banks to ratchet interest rates back up again if they fear inflationary pressures later this year. Higher interest rates cause people and businesses to spend less money, because the cost of borrowing is higher.

For a more detailed discussion, see InflationData.

Opportunity Cost

As an individual, I have limited income, that I allocate between spending on my wants and needs, while also saving and investing for the future. I can’t have everything I want, so I make choices that make me happiest. Factories need to allocate their resources – money and labour from their workers – to get the maximum production output.

Opportunity cost is the value of the next best thing that you have to give up, in order to get something else. It’s the value of the path you didn’t take, when you came to a fork in the road.

This can be a very challenging decision-making process. If you’ve ever watched a 7-year-old in a toy store deciding how to spend their allowance, you and see how hard it is for them to pick one and turn down another coveted toy!

Our next best alternatives can also be thought of in terms of our careers. For instance, you may weigh the choice to stay with your current job, or go back to school with the expectation that you will earn more later.

In terms of the current COVID-19 pandemic, we as a society have determined that the opportunity cost of shutting down all non-essential goods and services is better than the long-term cost of doing nothing and letting the virus run amok.

Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage means that one region is more efficient at producing a good or service than another region. All regions can benefit from cooperation and trade, by specializing in the products where they have a comparative advantage. They will export the good or service they specialize in, and import goods produced by other regions.

During coronavirus, we have seen how supply chains have been disrupted from countries that specialized in a good or service or component part of the production process. An early example is when China shut down factories during their lockdowns in January and February, while the rest of the world was still business as usual. But supplies needed from China were delayed or hard to obtain. We have also seen this when one country specializes in production of a product which has experienced greater demand, such as ventilators and N95 masks. Government policy may attempt to prevent exports to other countries.

This brings up the question of whether each region should be self-sufficient in a few basic production needs, to eliminate reliance on other countries during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though it is not economically justifiable from a comparative advantage point of view.

Pingback: How Will The Economy Impact You Post-Coronavirus | Kari » Millennial Money Podcast